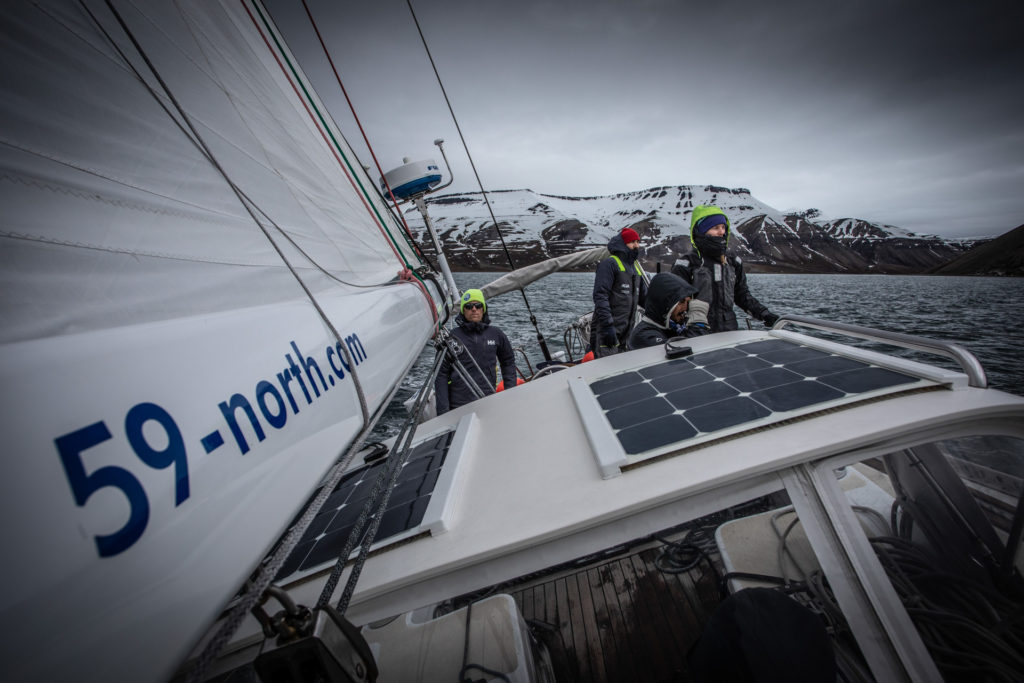

Ah, it feels so good to be back in cold weather. I’m bundled up and sitting on the rail of Isbjörn.. My entire body covered in layers upon layers and my face tucked away from the biting wind. My hair peeks out and flutters against my glasses, their polarization dramatizing the already extremely dramatic environment which lay before me. I close my eyes and let the never setting sun warm me, or at least trick me into thinking so. They flick back open and focus on the foggy clouds which are water falling over the ancient snow covered peaks. It as if they yearn to blanket the mountains which lie permanently frozen. The entire scene feels like one vast canvas, on which mother nature experimented with patterns and textures of an ice cool pallet.

It’s been six days since arriving inside the Arctic Circle, but it’s still hard to comprehend that we are actually here. Sailing in the cold is exhausting, a similar feeling to the one I have after surfacing from a scuba dive. When my body has been in survival mode for an extended period, matched with extreme wonder and awe. Because people weren’t really built to be underwater or in the Arctic. Yes- we have done it, but not without the help of the animal skins of the past or the technological clothing of today. Our modern weather forecasting, accurately detailed charts, and trusty radar allow us to understand and predict the world in a way we could not do solo. So it does feels slightly absurd to be up here, to be sailing around the glaciers of Svalbard. But, as unnatural as it is, it also feels very human. Because as a species, this is what humans do. They seek to bend the constraints that nature has over us. They strive to push it further- into outer space, to the depths of the ocean and the poles of our world. Faster, smarter, smaller, more efficient with each expedition. Even exploring our own fascinating minds is something that humans are always attempting, through altered states of consciousness, ego death, psychedelic expansion, meditation, so on and so forth. We as a species have always had the tendency to seek the unknown, explore the unexplored. So all I can do is smile, because in this moment I feel proud to be human.

My mind drifts back to the afternoon we just spent with a herd of Walrus on the beach. Some local sailors had told us about a resident “huddle” that lived around the Poolepynten headland on the Eastern coast of the Forlandet National Park. The Isbjörn crew had already seen some in the Southern part of Svalbard prior to our arrival, but it would be the Delos Crews first encounter with these gargantuan creatures. We had been warned to be cautious of them in the water, as a territorial male was more than capable of popping a rubber dinghy with their meter long tusks. So, we approached attentively and made our way around a group of four mingling in the water just off shore.

One thing I appreciate about Andy and Mia, is their utmost respect for the nature of the area. Traveling by sailboat creates a rare opportunity to explore a place without harming it. The crew’s mutual understanding and pride in this, allowed us to agree on how to best interact with the wildlife. So, we followed the recommend rules with the Walrus- we approached slowly from down wind, and kept a safe distance by capturing the moment with our long lenses.

The excitement built as we approached a pod of almost fifteen bulls relaxing on the sandy beach. We giggled as a particularly larger one attempted to make his way out of the water. It quickly became clear that lugging around a ton and a half of body weight with no legs, can be quite difficult. He used a combination of full body rolls and a worming movement, matched with constant grunting. Despite the interesting smells that protruded from them, what ensued after that was pure comedy. The big herd of males would work on getting as close as possible to one another. Their massive scarred bodies appeared to be melting in a puddle around them, with an undersized head floating somewhere on top. Just as everyone settles, one bull would rear with with a roar and stab his ivory tusks into his closest buddy. This would set off a chain reaction of jabs throughout the group, followed by more cuddles and lots more interesting sounds from both ends.

The laughs and observations of the hilarious Walrus have been continuing amongst us as we sail back across the strait of Forlandsundet towards Spitsbergen. We’ve just arrived at our anchorage in front of a miniature peninsula, which is guarding the Dahlbrebukta Glacier behind it. There are a few small chunks of ice floating around the boat, but not enough to for a crew member to stay onboard and “ice defend”. We are hopeful that a hike top of the peninsula will get us a good view of the glacier, so we decide to head in.

It’s quite a scene to watch us all gear up and get off the boat. Our crew of eight first attempts to find their driest base layer, then pulls on a mixture of wool mid-layers, before configuring some combo of our foul weather gear on top. Then comes packing the camera bags. Most of us are carrying a stand-alone production unit on our backs to be prepared for whatever shot may present itself. Between Canon, Panasonic, Sony, and DJI- we have most of the bases covered. We also always take survival suits in case the dinghy fails, flare guns to scare away curious polar bears, and a med kit in case someone is injured. We also have safety equipment with us like snow goggles, gloves, spiked boots, and so on. Last but not least, we load two rifles and decide which of the permitted crew will be taking a gun instead of a camera. I like to think the designers of the Swan 48′ would be proud to see how well she hosted us in circumstances she was so oppositely created for.

We load up the dinghy, and make the half mile trip two times to get all of the people and gear on land. Everyone makes it to the top well before me, and sets up our little day camp. The tripods go up, the moonshine comes out, and everyones laughter seems to hang a bit longer in the windless sky. I look up at and enjoy the view of the midnight sun silhouetting the crew, and pull my camera to my eye with a smile. Being behind the lens here is a true photographer’s delight for a very long list of reasons. My favorite, is that the sun appears to always be rising or setting, along some bold mountain skyline. A never ending “golden hour” of light which sets the scene for endless sun flares and dramatic back lighting. I make my way up to them, when-

BOOM! A clap of thunder erupts from the glacier which has just come into my view. I gasp in surprise as a massive chunk calves off and splashes into the sea water below. No one could ever be convinced of how loud this event truly is, until you hear it with your own ears. It’s echo lives on as it bounces around the mountains and makes us feel ridiculously small. Then, the several tons of ice create a tidal wave which swells up across the lagoon in our direction. It’s as if an arctic sea creature has been awakened from its sleep, and is quickly gliding just underneath the surface to devour us. But alas, no sea creature is revealed as the waves break below us with a crash.

I’m not sure how long we spent up there. It’s hard to keep track of time when the sun spins around you at a constant height. When 4am and 4pm look, feel, and act the same. Time is beginning to feel irrelevant. It seems everyone is adjusting to this differently, but I’ve realized how much my body depends on the natural cues of the sunrise and sunset. Although I can’t deny the perks of having constant daylight for this expedition, it would be a lie to say I am not missing the presence of the moon and stars.

The buzzing of several drones pulls me back from day dreaming about the night sky. The boys are flying about, and getting a kick out of the virtual reality head set at 200 meters above sea level. Turns are taken by all, putting it on and yipping in delight at the view from the sky. With it, we can now see beyond the front face of the glacier, and realize the true scale of it. It’s truly astonishing at just how much you can learn and see from having access to drones. I just can’t believe how big the glacier actually is. It goes on for what seems like an eternity, a body of icy white terrain rolling back for as for as far as the eye can see. How long has it been frozen in this way? How long will it remain? BOOM! Another colossal chunk breaks away and in just a moment transitions from a million year old glacier, to just drops in the ocean.

It’s my turn to play with to Mavic drone, so off I fly away from the glacier and towards Isbjörn. As I approach, my heart begins to beat faster at the breath taking sight. She is now surrounded by big chunks of ice, spread across a gradient of emerald green leading into a deep sea blue. I can’t believe I get to witness this moment first hand, that I get to capture it and save it forever. My jaw is dropped, heart is full, and all expectations for the trip are met here and now.

I call Andy over and give him the VR goggles to let the him fawn over the beauty of his boat. “WHOA!” he exclaims in excitement, which lasts but a brief moment. The smile slides off his face as the Captain in him realizes that any of those ice chunks could actually dangerously large under the surface. Isbjörn isn’t just their boat, their home ,and their life. It’s the key asset to a business that is already booked for the next several years. Taking this fiberglass boat up into Arctic waters did not come risk free, and keeping her and us safe is the number one priority of the trip.

He slips the goggles off immediately, and tells Mia it’s time to go. The rest of us gather our gear and head down the hill behind them. The adrenaline starts to pump. As we make our way down, or view changes to reveal a huge tidal stream of ice creeping its way straight towards Isbjörn. We span the exact same beach that we had crossed on our way over, only now it appears completely different. A hundred times more ice litters its shores and waters. Although we are in a rush to get back, I cannot help but capture this moment. I drop my bag to the ground and pull out my long lens. Half running to catch up, half screaming inside, I must have snapped 500 photos as I ran across that little beach!

It was in this moment that I recalled something a friend had told us, “Svalbard is like Iceland on crack”. Having spent a couple of weeks in Iceland before coming to the proper Arctic, I found this statement very hard to believe. But now, I find the truth.

As I make my way over the last small mound of dirt I hear Andy yelling from the dinghy, “All aboard, we need to go NOW!” We pile in and head back to the boat, whose anchor is now up as she slowly weaves through the icy waters with Mia at her helm.

Just as I climb aboard, James pops his head through the companion way. Through a toothy grin he exclaims that he would like to get in the water with his housing and dry suit. “ME TOO!” I think… But I did not come as prepared as James, and without a dry suit I will have to suffice with a pair of 3mm gloves as I hang over the side of the dinghy. I hop back into the tender with Brian as James jumps into the icy waters surrounding the boat. We cruise around and film the action, attempting to hold onto my camera against the big blocks of ice smashing into it. All hands on deck are standing at the bow with the ice poles to push away the largest pieces. Isbjörn slowly makes her way out of the tidal flow of ice, and into clear safe water.

This was just one day of our adventure in Svalbard. Although we had so many other unique experiences, I will never forget the feeling of this day. That raw emotion of excitement when the elements drastically morph right before your eyes. It must be why people become obsessed with high latitudes once they get a taste- because a feeling like that is sure hard to beat.